Essay by Jon Leaver, Associate Professor of Art History

Since emerging in the late 1960s and early 1970s, site-specific installation art has sought to reject the notion that artwork is independent of its surroundings. In line with this current in contemporary art, this exhibition brings the life of the street directly into the gallery – an impulse implicit in the work of the pioneers of site-specific work, many of whom worked in the local area. Appropriately, then, this exhibition brings together the diverse practices of two Los Angeles artists, Bettina Hubby and Chad Attie, both of whom explore the rich source of imagery to be found in their immediate locations: in the streets, thrift stores, parks, buildings and construction sites of the city. The gallery space itself is also meaningful since, in addition to the work of each individual artist, it accommodates a site-specific, collaborative installation, forming a visual dialogue between the two.

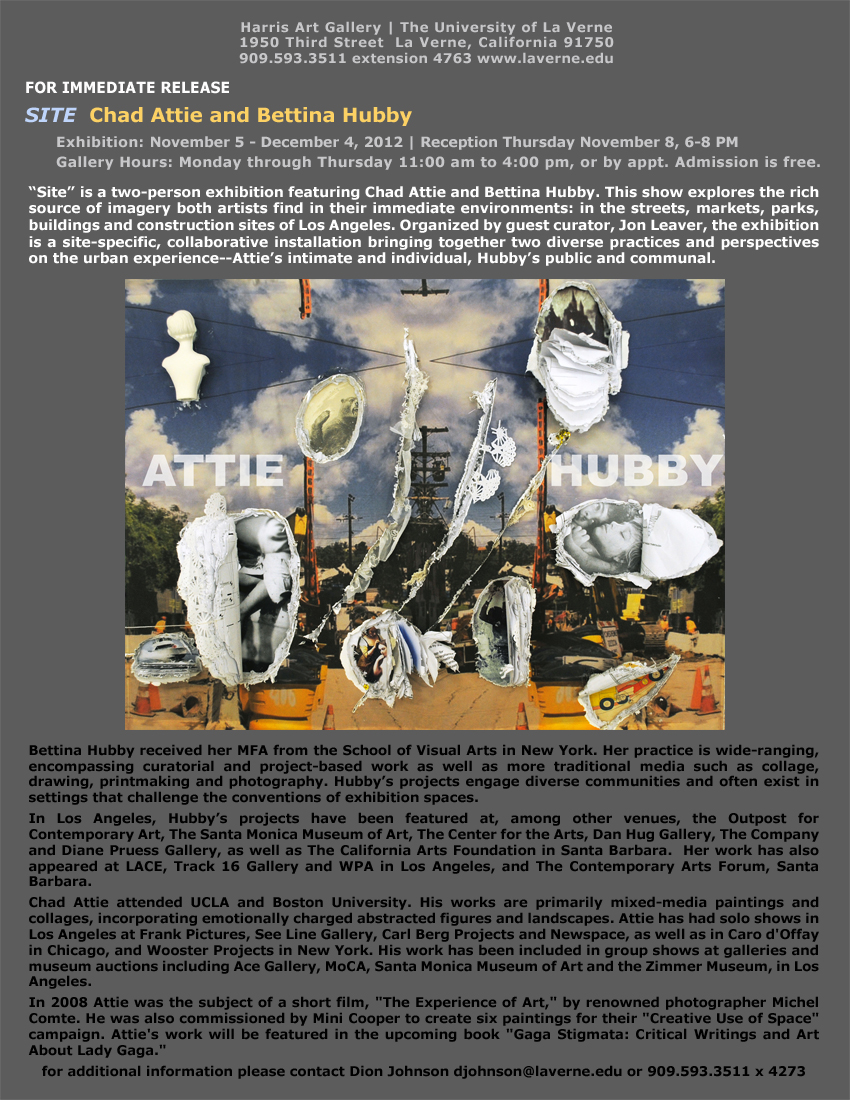

Hubby’s inspiration for the Construction Site series came literally from the street outside her front door. The imagery incorporated into her photographic and mixed-media installations derives specifically from the road works taking place on Rowena Avenue in Silver Lake, the site of her studio. As with much of Hubby’s work, the project is participatory and inclusive; for her the construction site is not a distant subject of her disembodied lens, but something to be engaged. Accordingly, she has brought the work site into the gallery in the form of five sections of chain link fence, onto which are clamped delicate silk panels printed with her photographs of construction work. These photographs are manipulated to subtly kaleidoscopic effect, producing a mirroring similar to a Rorschach inkblot, an invitation to the spectator, perhaps, to imbue the work with personal meaning. Other works in the show include ceramic tiled panels that further evoke and aestheticize the paraphernalia of road works, as well as photo-collaged wall decals depicting strange hybrids, conjoining organic forms and machinery.

Likewise, the dense assemblages of Attie’s Eden series are composed from imagery that is de-centered – often discarded or overlooked, the byproducts of more culturally central practices. Using architectural blueprints, secondhand book illustrations, thrift store paintings and much else besides, Attie creates multi-layered, collaged relief sculptures. Layers of paper and other materials are peeled back to reveal underlying strata, suggesting an archeological or geological approach to the experiences they evoke. Events accumulate in layers, only to erupt along emotional fault lines, or are excavated in memory. The clear acrylic boxes that cover the works add a further dimension, hinting that such memories remain untouchable – the remnants of an unalterable past which, nevertheless, the artist continually attempts to recapture and contain. Unlike the outward looking and highly social nature of Hubby’s work, Attie’s is intimate and personal, suggestive of a private, compulsive world of ideas. Yet in spite of the individualized nature of Attie’s work, his pieces also function, as Hubby’s do, as indexes for the city that exists outside the gallery.